For the first time ever, a cruise passenger of PONANT’s Le Commandant Charcot was able to navigate through the frozen Weddell Sea Ice to Snow Hill Island to meet a colony of thousands of Emperor Penguins.

Julie Rogers of PONANT walked 2.5km inland on Snow Hill Island to see the largest breeding colony, with thousands of Emperor Penguins, whilst travelling onboard Le Commandant Charcot in November. “I have travelled to Antarctica several times already, but have never seen the elusive Emperor Penguins, it has always been a dream of mine,” explains Julie.

Le Commandant Charcot is the world’s only luxury ice breaker, so this is the only way to see Emperor Penguin colonies as a tourist without the assistance and disruption of helicopters. “Being able to disembark directly onto the ice and the privilege of walking on top of frozen sea ice direct to the colonies, truly is the ultimate polar exploration!” she added.

Whilst spending two days exploring Snow Hill Island and several Emperor Penguin colonies, below is what Julie learned from the Naturalists onboard Le Commandant Charcot.

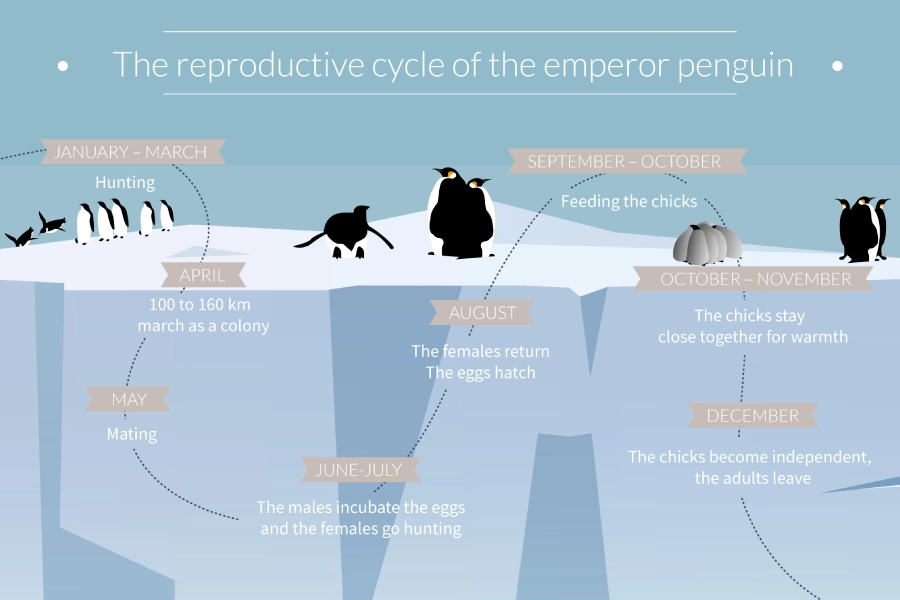

The Emperor Penguin is a unique seabird. While other animal species leave Antarctica during the winter, and other birds breed in the spring or at the beginning of the austral summer, the Emperor Penguin is the only animal species to breed in the middle of Antarctica’s austral winter, when the weather conditions are the harshest. But this strategic choice allows the young penguins to break away from their parents at the beginning of the summer when food is abundant.

Its reproductive cycle lasts a great deal of the year since it runs from March to December. After spending two months at sea stockpiling food, the adult Emperor Penguins arrive on the ice at the beginning of winter, when the sea ice starts creating ice jams. At the same time, other animals leave Antarctica in search of more lenient weather conditions.

After walking sometimes over a hundred kilometres on the sea ice, in columns hundreds of individuals strong, the Emperor Penguins make their way back to the colony, often made up of tens of thousands of birds. There are around sixty colonies of Emperor Penguins in Antarctica.

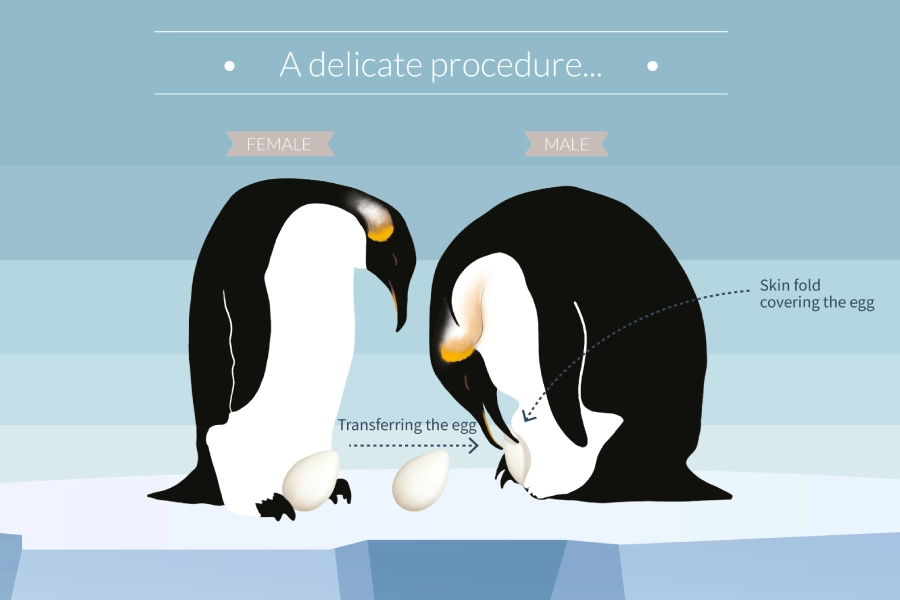

The couples then get together and the female lays a single egg between May and June. Once they have laid their egg, the breeding females leave the colony to return to the sea to feed, leaving the male alone to incubate the egg. The male incubates the egg by keeping it on its feet, well hidden under a fold of skin. This is a particularly crucial operation because, if the egg were to stay on the ice for too long, it would freeze almost instantly.

The eggs hatch in July. The females then make their return to the colony and feed their chick by regurgitating the contents of their stomachs. They can feed the chick that way for around a month. During that period, it is the turn of the males, who have fasted for over four months and lost up to 45% of their initial body weight, to take the silent road to the open water several kilometres away. They can then hunt, stock up on food, and come back to the colony to feed their young.

The breeding females and males, these indefatigable walkers, must travel several times between the colony and ice-free zones before the young become self-sufficient, in December when the ice breaks up.

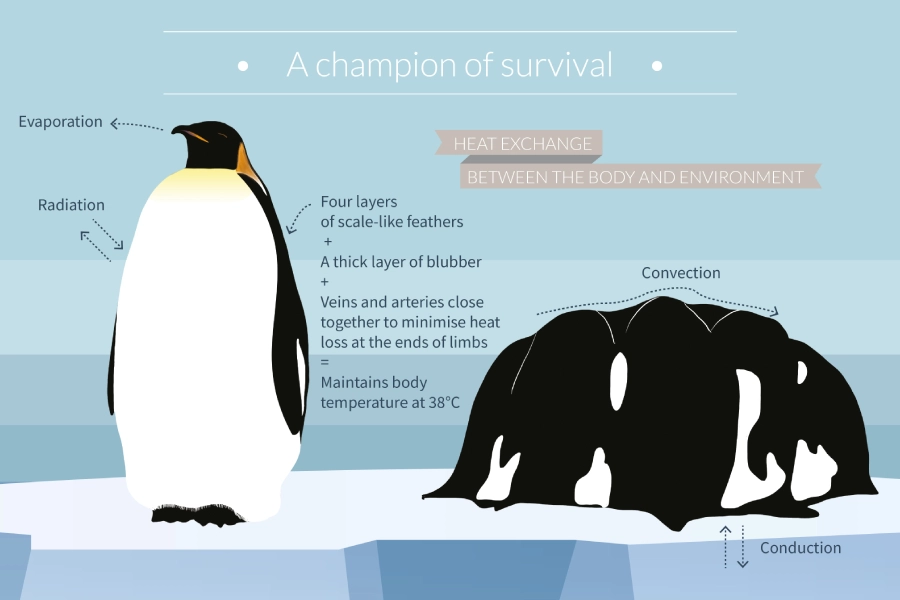

This breeding period during the austral winter makes the Emperor Penguin one of the warm-blooded animals to face some of the harshest weather conditions on the planet. How does it survive in such extreme conditions?

Its anatomy and behaviour are perfectly suited to survive on the ice. From an anatomical point of view, the penguin is equipped with many a tool to face the cold. It has four layers of feathers shaped like scales, a thick layer of blubber and a blood system that provides exceptional thermal insulation.

But it also managed to adapt its behaviour in order to survive. Emperor Penguins have evolved to stand in such a way as to limit the amount of body surface area exposed to the cold. They rest on their claws and on a layer of blubber under their feet, retract their necks and turn their backs to the wind. Furthermore, they are pacifists and one of the few bird species to not be territorial. This special feature and the fact they do not build nests, instead covering their egg on their feet, allow them to be constantly on the move within the colony. That way, they can engage in thermoregulatory behaviour, which is essential to their survival.

Indeed, Emperor Penguins stick together to form very dense groups known as turtle formations with a microclimate inside. This allows individual penguins in the centre to warm up, thus minimising heat loss. They swap places with each other, rotating between the centre and the outside of the formation. Once they become thermally independent, the chicks also adopt this behaviour. They join up to make nurseries and form chick turtle formations to survive temperatures that can drop below -50°C.

Le Commandant Charcot explores Antarctica in more depth than any other Expedition Vessel, travelling deep in the Weddell Sea and Larsen Ice Shelf and beyond the Antarctic circle through to the Ross Sea Shelf and Adèlie Land.

PONANT is offering Flight Credits of EUR3,000 per person for clients to join Le Commandant Charcot and explore Antarctica, choose from seven Expeditions in November and December 2023. Available for new bookings made before 31 January 2023.

Contact PONANT at reservations.aus@ponant.com or contact Julie Rogers directly at +61 455 129 990.